FAQs about Soliris

There is no known interaction between alcohol and Soliris. However, because alcohol can interfere with some medications, it is recommended that patients talk about this issue with their healthcare providers.

Animal studies have suggested that anti-C5 antibodies such as Soliris can cause fetal harm, but data from more than 300 women exposed to Soliris during pregnancy raised no safety concerns. Still, it remains unclear if Soliris can result in harm to a developing human fetus, so patients who become or plan to become pregnant while on the medication should discuss this topic with their physician.

Weight gain has not been reported as a side effect of Soliris in clinical trials of people with neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder. However, some trial participants given Soliris experienced reduced appetite and hair loss, and at a higher proportion than that observed in the placebo group. Patients should speak with their healthcare provider if they experience any unanticipated side effects with Soliris.

In the PREVENT trial, which supported Soliris’ approval for neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (NMOSD), significant differences in the proportion of relapse-free patients between the treatment and placebo groups were already evident after about 48 weeks, or nearly one year. However, each patient is unique and may respond differently to the medication; thus, individuals with NMOSD are advised to talk with their healthcare team to better understand how Soliris may help in their specific case.

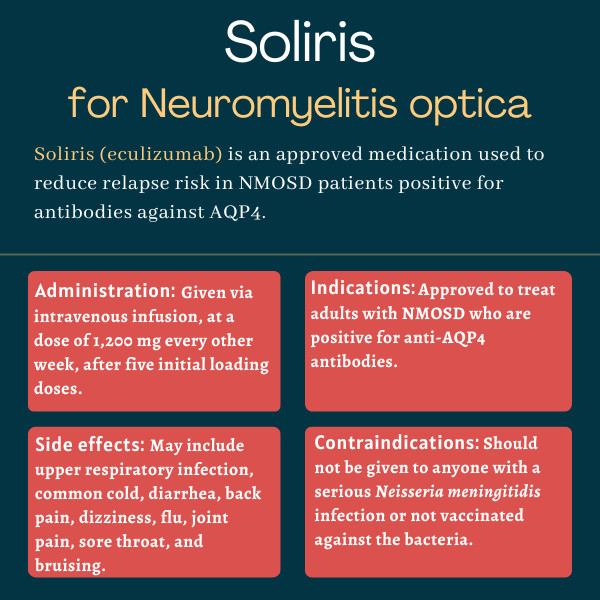

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved Soliris in June 2019 for adults with neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder who are positive for antibodies against the AQP4 protein. That decision marked the first FDA approval of a treatment for this rare autoimmune disease.

Related Articles

Fact-checked by

Fact-checked by