Inflammatory protein S100A9 ID’d as new treatment target in NMOSD

Abnormally high levels found in patients, linked to more severe disability

Written by |

People with neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (NMOSD) have abnormally high levels of S100A9, a protein that drives the inflammatory activity of certain immune cells, a study discovered.

According to the researchers, higher S100A9 levels in the blood were significantly associated with more severe disability among patients. These findings thus suggest that the protein may be a new biomarker for NMOSD research, as well as a therapeutic target.

“This study highlights S100A9 as a possible treatment target and a marker for predicting the disease, offering a new understanding of how NMOSD is diagnosed and develops,” the scientists wrote. Indeed, “targeting S100A9 may provide a new direction for the treatment of” the rare disease, the team noted.

The study, “S100A9 as a potential novel target for neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder,” was published in the journal Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders by a team of researchers in China.

NMOSD is an autoimmune disorder driven by inflammation that damages healthy nerve cells, particularly those in the spinal cord and in the nerves that connect the eyes to the brain. In most NMOSD cases, this damaging inflammation is caused primarily by self-reactive antibodies that target AQP4, a protein mainly present at the surface of nerve-supporting cells.

Nonetheless, many different types of immune cells are believed to be involved in NMOSD. Further, the specific molecular mechanisms underlying the disease remain incompletely understood.

In addition to the immune responses driven by anti-AQP4 antibodies, research so far has suggested that “immune cells such as monocytes/macrophages not only initiate acute-phase inflammation but also contribute to [nerve] lesions … highlighting their key [disease-associated] role in NMOSD,” the researchers wrote.

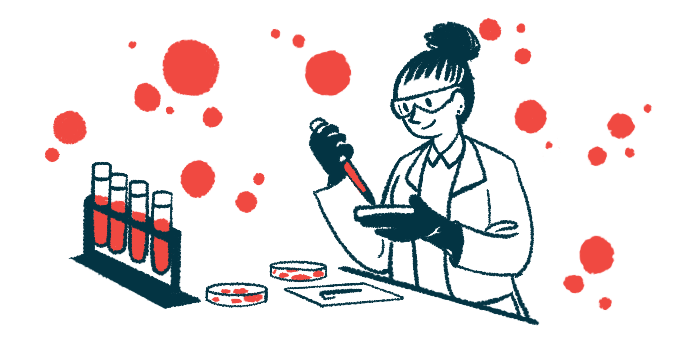

Scientists search for ‘hub genes’ that may drive disease

To gain more insight into the molecular underpinnings of NMOSD, a research team from The Second Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University conducted detailed analyses of genetic activity in immune cells. The scientists collected the cells from 25 people with the autoimmune disease and 25 age- and sex-matched healthy individuals, who served as controls.

Specifically, the team wanted to find so-called hub genes. The basic idea is this: If one dysregulated gene causes 10 other genes to also be dysregulated, then the original one has the most importance in terms of driving the disease.

These genes are called hub genes because, when scientists diagram how the different genes interact with each other, these critical genes end up at the center, with other genes surrounding them — much like spokes surrounding the hub of a wheel.

The genetic analyses identified 326 genes whose activity was significantly altered in people with NMOSD relative to healthy controls. Of the 38 genes related to immune functions, 10 were selected as potential hub genes.

Then, according to the researchers, “literature-supported evidence led to the selection of S100A9 as the key gene for further analysis.”

The team noted that activity of the S100A9 gene, which encodes for the S100A9 protein, was significantly increased in people with NMOSD, “but was barely detectable in [healthy controls].”

Suppressing S100A9 may be new treatment strategy in NMOSD

Protein analyses confirmed that S100A9 protein levels were significantly higher in the NMOSD group. Further, among the patients, higher blood levels of the S100A9 protein were significantly associated with more severe disability.

“These combined molecular and clinical observations indicate that elevated S100A9 … in [immune cells and blood] may serve as an important biological marker in NMOSD patients,” the researchers wrote.

Testing was done with lab-grown macrophages from both groups. The team found that S100A9 is produced by these immune cells during the early inflammation stage of NMOSD. Also, when macrophages were exposed to increased levels of S100A9, they grew faster and started to produce proinflammatory signaling molecules.

The researchers specifically determined that S100A9 was triggering this inflammatory state in the macrophages by activating TLR4, a receptor protein involved in inflammatory responses.

Based on these findings, the researchers proposed that high S100A9 levels in NMOSD may trigger inflammatory activity from macrophages, which could play a role in disease progression. As such, treatments aiming to block S100A9, or the receptor protein TLR4, might reduce NMOSD disease activity, according to the team.

These data suggest that modulation of S100A9 offers a novel avenue for NMOSD treatment, but further interventional studies with larger [patient groups] are necessary to conclusively determine whether S100A9 [suppression] is an effective therapeutic strategy.

The researchers stressed, however, that a lot more research will be needed to validate these findings and test this approach before the work can be translated into human medicine.

“At the cellular level, the present study identifies a proinflammatory role for S100A9 in NMOSD,” the researchers wrote. “These data suggest that modulation of S100A9 offers a novel avenue for NMOSD treatment, but further interventional studies with larger [patient groups] are necessary to conclusively determine whether S100A9 [suppression] is an effective therapeutic strategy.”