Aseptic Meningitis, Epstein-Barr Implicated in Rare Case of NMOSD

Aseptic meningitis complicates, delays NMOSD diagnosis in 72-year-old man

Written by |

A man’s first manifestation of neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (NMOSD) was aseptic meningitis, an inflammation of the meninges (the membranes that enclose the brain and spinal cord) without evidence of a bacterial infection, which is unusual and made a quick diagnosis difficult, says a report from Japan.

The man tested positive for self-reactive antibodies against aquaporin-4 (AQP4), which are known drivers of NMOSD, and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV). The virus was most likely not the cause of aseptic meningitis because it was present in blood but not in cerebrospinal fluid (the liquid that cushions the brain and spinal cord). However, it may have had a part in the pathogenesis of NMOSD, or the chain of events leading to the disease.

“This report highlights the importance of considering AQP4-related NMOSD as a differential [diagnosis] for aseptic meningoencephalitis syndromes and the possible role of EBV in their pathogenesis,” its authors wrote.

The report, “Anti-AQP4-IgG-positive neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder presenting as aseptic meningitis following Epstein–Barr virus infection,” was published in the journal Neuroimmunology Reports.

NMOSD occurs when the immune system makes self-reactive antibodies that turn against myelin, a fatty substance that sheathes the nerve cells, and damages the spinal cord and the optic (eye) nerves.

Patients with NMOSD may experience a wide range of symptoms from eye pain and poor eyesight to weakness, loss of coordination, and changes in sensation. Some also experience transverse myelitis, which happens when the spinal cord becomes inflamed.

In NMOSD, what triggers recurring attacks is unclear and can be different for each patient, but some harmful germs may play a role.

Epstein-Barr virus may have part in immune changes leading to NMOSD

One such germ is EBV, a common virus that can cause mono, which is short for infectious mononucleosis, and other diseases. Roughly half of patients with NMOSD in a study were found to have active viral replication, which is the process by which the virus makes copies of itself in its host. This means that EBV may have a part in the immune changes that set off NMOSD.

(Of note, being infected with EBV has been found to raise by 32 times the risk of developing multiple sclerosis, another autoimmune disease where there is damage to the myelin sheaths around nerve cells.)

In the new report, a team of scientists in Japan documented the case of a 72-year-old man who was diagnosed with NMOSD following an infection with EBV. His first manifestation was aseptic meningitis, which delayed the diagnosis. Aseptic meningitis has previously been linked to NMOSD in four reports, the team noted.

The man went to the hospital with a fever and headache lasting for one week. He was gradually losing consciousness.

A sample of cerebrospinal fluid revealed too high a number of cells and proteins. Based on these findings, doctors in another hospital had suspected a herpes simplex virus or varicella-zoster virus infection, and had started treatment with acyclovir, and antiviral medication.

However, the patient’s consciousness level did not improve. When he was brought into the new hospital, he had inappropriate speech, and was able to move and opened his eyes only in response to pain.

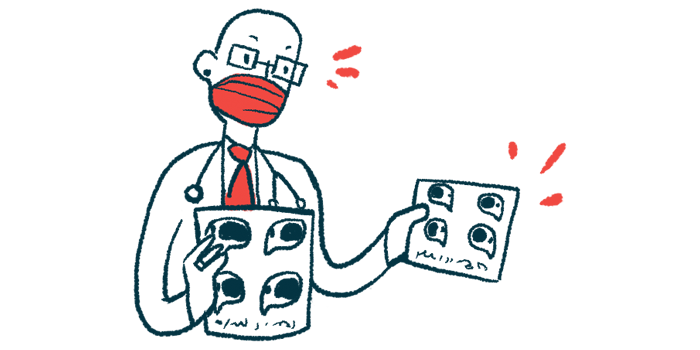

An MRI scan of the brain revealed enhancement (a bright signal) around the brain’s surface and along the lining of the ventricles that are filled with cerebrospinal fluid.

The doctors thought this might indicate an inflammation secondary to a cytomegalovirus infection. They switched the treatment to ganciclovir, another antiviral medication, but saw no improvements. Tests for the suspected viruses came back negative, and the treatment was stopped.

Another MRI scan, this time of the spinal cord, revealed longitudinal extensive transverse myelitis, which occurs when damage to the spinal cord extends over three or more vertebrae. The man was treated for three days with intravenous (into-the-vein) methylprednisolone, a corticosteroid. “However, his consciousness level remained poor,” the team wrote.

A test for EBV revealed its presence in the blood but not in the cerebrospinal fluid, which indicated that the virus was not the cause of aseptic meningitis.

The man had developed antibodies against the viral capsid antigen, which usually appear early in an infection. Antibodies against the EBV nuclear antigen, which usually appear two to four months after an infection and persist for the rest of a patient’s life, were initially absent but appeared after two months. These findings indicated that the infection was recent.

Patient treated with intravenous immunoglobulin and immunosuppressants

A new MRI scan again showed enhancement along the lining of the ventricles, and a close look at a sample of brain tissue revealed loss of myelin around nerve cells. A test for anti-AQP4 antibodies came back positive.

The man was given intravenous immunoglobulin, a treatment that uses a pool of antibodies from donated blood to help the body fight off an infection, and a second course of intravenous methylprednisolone. Plasmapheresis, also known as plasma exchange, was not an option because of the man’s poor general health.

While the case did not prove it, EBV can attack B-cells, a type of immune cells, and this could be enough to force them into making self-reactive antibodies such as those causing NMOSD, the team noted.

At the time of writing of the report, the man was still being treated with prednisolone and azathioprine, an immunosuppressant. His symptoms had not returned, and the number of EBV copies had not increased for one year.