Prednisolone may help slow the loss of brain white matter in NMOSD

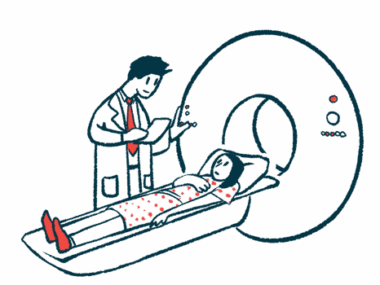

Brain MRI scans show faster loss of white matter volume in patients in study

Written by |

Neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (NMOSD) is associated with a faster loss of white matter volume in the brain, but taking the corticosteroid prednisolone may help counter this effect, according to a small study in Japan.

The brain’s white matter contains the long, wire-like projections, or fibers, that nerves use to communicate with each other and to connect different regions within the brain.

These preliminary findings suggest that suppressing inflammation and disease activity with available treatments may help slow white matter loss in NMOSD patients, researchers noted.

The study, “Higher longitudinal brain white matter atrophy rate in aquaporin-4 IgG-positive NMOSD compared with healthy controls,” was published in Scientific Reports.

Damaging inflammation in NMOSD can affect eye nerves and spinal cord

NMOSD is a rare autoimmune disease characterized by self-reactive antibodies that mistakenly attack the body’s own nervous system cells, causing damaging inflammation that affects mostly the eye nerves and the spinal cord.

As such, people with the disease usually experience problems with vision and movement. Also, each inflammatory attack can cause new neurological damage that builds up over time, often leading to greater disability.

While NMOSD-associated disability is generally considered to be dependent on attacks or relapses, increasing evidence suggests that patients may experience brain volume loss without noticeable symptoms.

In a previous study, a team of researchers in Japan showed that silent brain atrophy or shrinkage was occurring over time even in NMOSD patients with clinically inactive disease. Notably, patients with long spinal cord lesions showed faster atrophy of the brain’s gray matter, which corresponds to nerve cell bodies.

However, that study compared brain volume changes over time between NMOSD patients and people with multiple sclerosis, another autoimmune disease that affects the nervous system. A comparison group composed of healthy people was lacking.

Study compared brain scans from NMOSD patients, healthy people

To address that limitation, and because brain atrophy is also a normal part of aging, the same team has now compared brain scans of 29 NMOSD patients with those of 29 age- and sex-matched healthy people to understand if the disease speeds brain volume loss.

All participants (75.9% women) were recruited from the Japanese Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative study and another study performed at Chiba University, in Japan. All had two brain MRI scans taken at an interval of more than one year in the same scanner.

All NMOSD patients tested positive for antibodies against the AQP4 protein, the most common target of NMOSD-driving self-reactive antibodies. At the time of their first MRI scan, they had lived with the disease for a median of seven years.

Patients were started on prednisolone, a corticosteroid that helps ease inflammation and damage, a median of 3.9 years before. The median time since the last attack was 2.8 years.

At the first MRI scan, 20 patients were on prednisolone alone, three took prednisolone and azathioprine, and one was being treated with prednisolone and Soliris (eculizumab). Five patients did not receive any medication to prevent relapses.

At the second scan, azathioprine had been added to the treatment regimen of one of the patients treated with prednisolone alone at the first scan.

The interval between the first and second MRI scan was a median of about 3.6 months longer in the NMOSD group relative to the healthy control group (3.2 vs. 2.9 years).

Most patients showed similar trend in brain atrophy between MRI scans

“Most patients showed a similar slope for changes in brain atrophy between MRI-1 and MRI-2, regardless of the disease duration,” the team wrote.

The researchers calculated the annualized brain atrophy rate, or percentage of volume lost from one MRI scan to the next, adjusted to a one-year period. For each person, this rate was adjusted to the total volume within the skull.

The researchers found that the annualized atrophy rate of total brain volume and gray matter volume did not differ between NMOSD patients and healthy people, but that of white matter volume was significantly greater in the NMOSD group.

This is in contrast with earlier findings that NMOSD patients had smaller total brain volume and gray matter volume than people without any neurological disease, suggesting faster loss with NMOSD. However, in that study, NMOSD patients were older than healthy controls, which may have influenced the results.

No significant differences were detected between female and male patients in terms of all three brain volume measures and their respective atrophy rate.

Most NMOSD patients (86.2%) had inflammation of the spinal cord, and nearly two-thirds (62.1%) had long spinal cord lesions.

Those with longer spinal cord lesions before their first MRI scan also had smaller white matter volume on that scan, but “no associations were found between the spinal cord lesion length and annualized atrophy rate of each brain volumes,” the researchers wrote.

Being on prednisolone longer linked to slower rate of white matter shrinkage

Being on prednisolone for longer, measured at the time of the first and second MRI scans, was linked to a slower rate of white matter shrinkage.

“These results suggest that inhibiting relapse and inflammation lowers subsequent brain white matter atrophy rates in patients with [AQP4-related NMOSD],” the researchers wrote.

In other words, initiating anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive treatment as early as possible may help preserve the brain’s white matter in these patients.

These findings also suggest that “subclinical active lesions may be involved in brain white matter atrophy” in AQP4-related NMOSD, the team wrote.

“Future studies with a higher number of patients, different ethnicity groups, adjusted [potential influencing] factors, and a unified MRI scanner are required” to confirm these findings and assess whether other immunosuppressive therapies have the same protective effects, the researchers concluded.