Disability, depression after NMOSD diagnosis likely lead to job changes

Researchers: 'Robust' guidelines needed to protect against discrimination

People diagnosed with neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (NMOSD) who lose their jobs or cut back on their hours likely contend with vision loss, worsening pain, the use of walking aids, and frequent fatigue or depressed mood, an international study reports.

“Developing a robust set of disability guidelines to protect patients against workplace discrimination … along with producing new treatments for major disease symptoms, could help alleviate some of the issues highlighted in this study,” the study’s researchers wrote. The study, “Unemployment, work hour reduction, and income loss: An international, multicentered, cross-sectional study of neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder,” was published in Multiple Sclerosis Journal. It was funded by the nonprofit Sumaira Foundation and Amgen, which markets the NMOSD-approved therapy Uplizna (inebilizumab-cdon).

Job trends like these were generally consistent across countries and other demographic variables, but employment rates were lower for women and people in lower-middle income countries.

NMOSD is a chronic autoimmune condition wherein the immune system attacks healthy cells in the spinal cord and optic nerves, which help carry information to and from the eyes. The resulting inflammation and damage can lead to problems with movement and vision, along with fatigue, pain, and mental health concerns.

“These deficits could impact adults of working age in work contexts, influencing their ability to work and earn income,” wrote the researchers, two of whom completed a previous study that found loss of work, hours, and wages for U.S. residents after a NMOSD diagnosis. For them, problems with movement and vision impacted their productivity, as did pain and fatigue.

Impact of NMOSD on work and workers

Here, researchers sought to characterize NMOSD’s impact on employment, work hours, and wages in patients around the world. The patients were asked by neurologists across 23 countries to complete a 65-question survey that included questions about demographics, clinical history, symptoms, and employment. A total of 897 people (81.4% women) completed the survey. The respondents had a mean age of 42.5 at their enrollment and a mean disease duration of 7.6 years. From China, 199 people responded, as did 102 from the U.S., 76 from India, and 70 from Iran.

Common clinical features included vision loss (34% in one eye, 28.2% in both eyes) and spinal cord inflammation (58.9%). More than a third reported using walking aids.

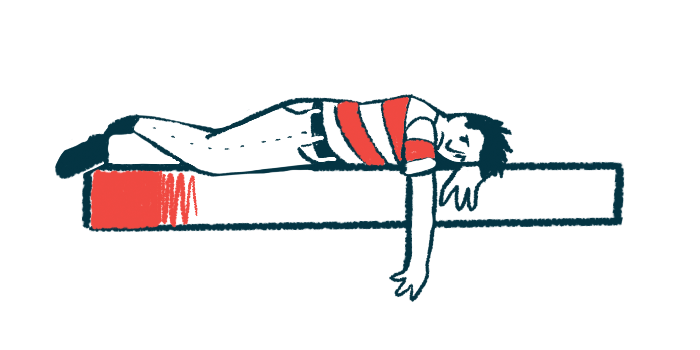

The participants rated their pain at a mean of 4.5 on a scale from 0 to 10, with more than half saying pain affected their ability to work. About 21% said they almost always had fatigue and about 18% said they had periods of depression nearly every day.

Before their diagnosis, 62.7% had some employment, including full-time, part-time, or self-employed work. After it, this rate dropped to 36.3%. Their average weekly working hours also decreased from 32.8 to 16.3. Of the 321 participants with health insurance through work, 82.2% said it was why they continued working.

Being older, a woman, having fewer years of education, living in a lower-income country, having bilateral vision loss, a depressed mood nearly every day, and using walking aids were independent predictors of unemployment. Living in a higher-income country, having vision loss in just one eye, frequent fatigue, more pain, and being frequently depressed were predictors of lost or reduced work hours after a diagnosis. Also, older age and frequently being depressed predicted a decline in wages.

“Employment was associated with various demographic … and clinical … variables, while the loss and reduction of work hours were associated primarily with clinical factors,” the researchers wrote. “Understanding how pervasive and significant gender disparities in employment are can help elucidate, in part, why it emerges as such a strong predictor in our (and any) employment model.”

Despite many losing work or hours, and nearly half reporting losing wages, the median yearly income increased after a diagnosis. Inflation trends and wage increases for people who continued to work could help explain these findings, according to the researchers, whose statistical models didn’t account for these variables. Another possible study limitation was the participant recruitment strategy, which relied on neurologists.

“By virtue of having access to neurological care, being treated, and able to complete our survey, our participants were likely better off than the general NMOSD population,” they wrote.

This could mean the study underestimated the effects of a NMOSD diagnosis on employment. The researchers said accessibility accommodations and anti-discrimination measures could help people with NMOSD retain employment and continue other socioeconomic activities. Also, “better treatment of pain and depression could potentially alleviate negative employment outcomes, as compared to some of the physical limitations of NMOSD, such as vision loss, that are more irreversible and lack effective treatments,” they wrote.