Brain, spinal cord shrinkage linked to distinct NMOSD outcomes: Study

Different atrophy patterns in nervous system lead to discrete problems

Different patterns of shrinkage in the brain and spinal cord are associated with distinct clinical outcomes in people with neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (NMOSD), a study reports.

Findings suggest that NMOSD patients showing shrinkage, or atrophy, in outer brain regions are more likely to experience substantial physical disability and/or cognitive problems. In contrast, those with atrophy in spinal cord tissue are more likely to experience relapses.

The study, “Spatiotemporal subtypes of brain and spinal cord atrophy in neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders and multiple sclerosis,” was published in BMC Medicine.

Researchers used AI tool to identify patterns

NMOSD is an autoimmune disorder in which abnormal immune responses cause damaging inflammation, mainly in the spinal cord and optic nerves, which relay signals between the eyes and the brain. The resulting damage leads to atrophy in various regions of the central nervous system (CNS), or the brain and spinal cord.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a related but distinct autoimmune disease that’s also marked by immune-mediated damage and resulting atrophy in the CNS.

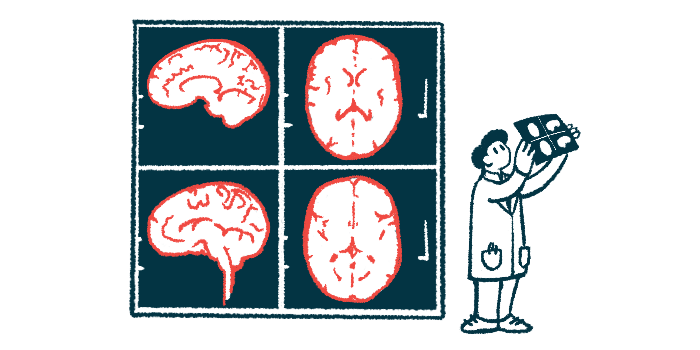

“Neuroimaging studies have demonstrated distinct brain and spinal cord atrophy patterns in NMOSD and MS,” the researchers wrote. However, there is still limited evidence on potential well-defined MRI profiles that align with different disease progressions, particularly in people with NMOSD.

With this in mind, a team of researchers in China analyzed clinical and MRI data from 278 NMOSD patients and 391 MS patients, as well as more than 1,000 people without neurological disease.

Understanding the distinct and shared atrophy patterns in NMOSD and MS can provide crucial insights into their differential disease progression and patient management.

Their goal was to understand how different patterns of CNS atrophy are associated with clinical outcomes across the two diseases. To achieve this, they utilized the Subtype and Stage Inference (SuStaIn) model, a specialized artificial intelligence tool that aids in identifying temporal and clinical/MRI patterns for any progressive disease.

“Understanding the distinct and shared atrophy patterns in NMOSD and MS can provide crucial insights into their differential disease progression and patient management,” the researchers wrote.

The median age of NMOSD patients was 43 years, and all were positive for self-reactive antibodies against the AQP4 protein, the most common type of antibody driving NMOSD.

About 60% of NMOSD patients showed CNS atrophy, which could be divided into three main patterns: cortical (31.3%), spinal cord (20.9%), and cerebellar (9.4%). The remaining patients showed normal age-related CNS shrinkage.

The cortical atrophy subtype was characterized primarily by atrophy in the outermost part of the brain, which is responsible for complex brain functions, while the spinal cord atrophy subtype exhibited atrophy mainly in the spinal cord.

The cerebellar subtype exhibited atrophy in different brain regions, including the cerebellum, in early versus late stages of the disease. The cerebellum is a structure at the back of the brain that is involved in coordinating voluntary movements, balance, and posture.

Most patients exhibited the same atrophy subtype at both study’s start and follow-up, or progressed from normal age-related pattern to one of the subtypes.

Patients with cerebellar atrophy pattern less likely to have worsening disability

Further analyses showed notable differences in clinical features based on atrophy patterns. Specifically, patients with a pattern of cortical atrophy tended to have more pronounced physical disability and cognitive issues, while those with spinal cord atrophy had a higher number of disease relapses.

By contrast, patients with cerebellar atrophy had a disability level and a number of flares generally similar to those with normal age-related atrophy.

Statistical models indicated that patients with a cerebellar atrophy pattern were significantly less likely to experience disability worsening and relapses over time compared with patients with cortical or spinal cord atrophy.

Models also indicated that treatments were less likely to be effective at preventing relapses in patients with cortical or spinal cord atrophy, compared with those who had normal-appearing atrophy.

The scientists also identified several different atrophy patterns among MS patients. The specific patterns across both diseases showed similarities as well as differences. For example, the researchers also identified subgroups of MS patients defined by cortical or spinal cord atrophy, though the specific parts of the brain involved weren’t totally identical.

The scientists noted that additional work is needed to validate and expand upon these findings, but they said that the different patterns of atrophy identified here “may provide a better interpretation of disease [variability] and help develop targeted management strategies.”